扩展功能

文章信息

- 乌吉斯古冷, 潘雅清, 胡金鹏, 张亚琪, 李斌, 刘建利, 康鹏

- Wujisiguleng, PAN Yaqing, HU Jinpeng, ZHANG Yaqi, LI Bin, LIU Jianli, KANG Peng

- 长叶红砂叶际细菌和真菌群落对季节变化的响应特征

- Response of phyllosphere bacteria and fungi of Reaumuria trigyna to seasonal change

- 微生物学通报, 2023, 50(1): 48-63

- Microbiology China, 2023, 50(1): 48-63

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.220376

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2022-04-12

- 接受日期: 2022-07-21

- 网络首发日期: 2022-09-06

2. 中国科学院西北生态环境资源研究院 沙坡头沙漠研究试验站, 甘肃 兰州 730000;

3. 兰州大学草地农业科技学院, 甘肃 兰州 730020;

4. 北方民族大学国家民委黄河流域农牧交错区生态保护重点实验室, 宁夏 银川 750021;

5. 北方民族大学宁夏特殊生境微生物资源开发与利用重点实验室, 宁夏 银川 750021

2. Shapotou Desert Research and Experiment Station, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu, China;

3. College of Pastoral Agriculture Science and Technology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730020, Gansu, China;

4. Key Laboratory of Ecological Protection of Agro-Pastoral Ecotones in the Yellow River Basin, National Ethnic Affairs Commission of the People's Republic of China, North Minzu University, Yinchuan 750021, Ningxia, China;

5. Ningxia Key Laboratory for the Development and Application of Microbial Resources in Extreme Environments, North Minzu University, Yinchuan 750021, Ningxia, China

植物叶际(phyllosphere)包括叶、茎、花和果实等组织与空气接触的表面部分,为微生物的定殖提供了多个生态位[1-4]。叶片作为叶际最主要的组成部分,大量微生物在此定殖并进化出适生能力[3, 5]。然而,植物叶际直接暴露于快速变化的环境之中,常受温度、紫外线辐射、营养胁迫、降水和干旱等环境变化的不利影响[1]。叶际微生物则通过植物产生的挥发性有机化合物(volatile organic compounds, VOCs)及植物生长调节剂等,不仅诱导宿主免疫系统抵抗病原体入侵,还可以帮助植物适应逆境[6-10]。此外,叶际微生物溶磷、解钾、固氮功能也是植物叶片获取营养的重要途径[11-12]。

较多研究表明,植物叶际微生物群落结构是动态的,寄主特性、植物地理分布格局、时间/季节性、环境变化等因素均直接或间接影响叶际微生物群落的多样性和群落结构[13-15]。其中,叶际细菌和真菌群落季节动态变化已在美洲黑杨(Populus deltoids)、银杏(Ginkgo biloba)、白皮松(Pinus bungeana)和杉木(Cunninghamia lanceolata)等植物的研究中得到证实[14, 16-19]。学者同时指出,叶际微生物区系结构和组成的改变受温度、湿度和太阳辐射水平的时间/季节变化调控[20-22]。另有学者发现,盐度增加和季节更替对菠菜叶际细菌群落组成和功能具有较大影响,而季节效应更为明显[23]。

尽管时间/季节变化调控植物叶际微生物群落形成机制的相关研究已取得大量进展,但大多数研究都集中在森林生态系统或室内栽培实验[24-26],限制了我们对荒漠植物叶际微生物群落构成的进一步认识,尤其是荒漠泌盐盐生植物叶际盐分动态变化对微生物群落结构的影响还有待深入研究[27]。鉴于此,本研究以盐腺泌盐植物长叶红砂(Reaumuria trigyna)为研究对象[28],通过春季、秋季叶际泌盐量测定和细菌、真菌高通量测序分析,探究不同季节叶际细菌和真菌群落对盐分变化的响应特征,以期加深对植物-微生物-环境相互作用的进一步认识。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究区域概况及样品采集研究样地位于内蒙古鄂托克前旗乌兰陶勒盖(E106°59'59";N38°32'36"),分别于2021年4月(春季)、9月(春季)进行取样(图 1)。取样时选择长势良好的红砂植株,先取长叶红砂灌丛下根区5−10 cm土壤,用于后续理化特性分析。然后用无菌剪小心剪取植株冠层处叶片,每株剪取20个叶片,装入含有50 mL无菌水的离心管中,取样植株相互间隔50 m,共取12个离心管样品,置于−4 ℃车载冰箱带回实验室。低温条件下,将样品进行超声处理(200 W, 3 min)后,取出植株叶片,使用无菌滤膜(0.22 μm)对叶际微生物的混悬液进行抽提、过滤,每3个滤膜混为一个样本,置于干冰盒中寄送北京诺禾致源科技股份有限公司用于样本DNA提取、PCR扩增和测序。滤液用于后续红砂叶际泌盐量的测定。

|

| 图 1 研究样地示意图 Figure 1 Distribution of the plots within the study area. |

|

|

纯水仪,四川优普超纯科技有限公司;超声波清洗仪,上海尚仪仪器设备有限公司;电子天平,梅特勒托利多仪器上海有限公司;烘箱,上海力辰仪器科技有限公司;火焰风光光度计,上海奥析科学仪器有限公司。

1.2 长叶红砂叶际和根际理化特性测定采用Pan等的方法[29],根据土水质量体积比(1:5)测定土壤的pH,以及土壤和叶际的电导率(electrical conductivity, EC);将土壤样品和超声处理后的植株叶片置于烘箱(80 ℃)烘干至恒重,通过火焰分光光度计测定长叶红砂根际和叶际Na+、K+含量。采用SPSS 25.0软件对数据进行单因素方差分析(analysis of variance, ANOVA),邓肯检验用于识别是否存在显著差异(P < 0.05),所有数据均以均数±标准误差(n=4)表示。

1.3 长叶红砂叶际细菌和真菌DNA提取和PCR扩增采用十二烷基磺酸钠法(sodium dodecyl sulfate, SDS)提取长叶红砂叶际细菌和真菌总DNA。采用引物338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGG CAGCA-3′)和806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTC TAAT-3′)扩增细菌16S rRNA基因的V3−V4区域,采用引物ITS5 (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTA ACAAGG-3′)和ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATC GATGC-3′)扩增真菌。PCR反应体系:10×Buffer 2 μL,dNTPs (2.5 mmol/L) 2 μL,正、反向引物(10 μmol/L)各0.8 μL,Phusion DNA聚合酶0.2 μL,DNA模板1 μL,ddH2O补足20 μL。PCR反应条件:98 ℃ 1 min;98 ℃ 10 s,50 ℃ 30 s,72 ℃ 30 s,30个循环;72 ℃ 5 min[30]。扩增产物纯化后进行文库构建,文库检测合格后使用NovaSeq 6000进行测序。DNA提取、PCR扩增和测序均委托北京诺禾致源科技股份有限公司完成。

1.4 长叶红砂叶际细菌、真菌多样性分析测序数据使用FLASH (V1.2.7)软件进行拼接处理,质控后利用UPARSE (V7.0.1001)对序列进行OTU聚类(97%相似度),并进行物种注释[30-31]。获得的数据上传至NCBI SRA数据库(序列号:PRJNA796741和PRJNA796745)。使用QIIME (V1.9.1)软件计算长叶红砂叶际细菌和真菌OTU、Shannon、Chao1和ACE指数并使用R (V4.1.0)语言中的“ggplot2”包可视化[32];采用“LinkET”包(https://github.com/Hy4m/linkET)计算并可视化细菌和真菌的α多样性与土壤理化之间的相关性;非度量多维尺度分析基于“vegan”包计算样本间的Bray-Curtis距离并进行相似性检验(analysis of similarities, ANOSIM),分析组间群落组成的差异[33-34];“NST”包计算细菌群落βNTI和RC值,“ggplot2”包可视化,分析群落的生态过程[35]。Cytoscape (V3.9.1)软件绘制不同季节叶际细菌、真菌共有和独有OTU数目;借助“ggalluvial”和“ggplot2”包对叶际细菌和真菌群落结构变化进行描述;“ggpubr”和“ggplot2”包进行菌属间的差异分析;“psych”和“ggplot2”包描述叶际细菌和真菌菌属同理化特性的相互关系[34]。

2 结果与分析 2.1 长叶红砂根际和叶际理化特性差异理化分析如表 1所示,春季长叶红砂土壤中的相对含水量显著高于秋季(P < 0.05),土壤pH、EC、Na+和K+含量均低于秋季。长叶红砂叶际EC、Na+和K+含量变化与冠下土壤相一致,秋季均显著高于春季。

| 指标 Indicators |

春季4月 Spring april |

秋季9月 Autumn september |

| 含水率SWC | 12.43±1.21a | 6.27±0.47b |

| pH | 8.25±0.13b | 8.8±0.11a |

| 根际EC Rhizosphere EC (µ/cm) |

94±9.21b | 310.5±19.84a |

| 根际Na+ Rhizosphere Na+ (mg/kg) |

135.67±17.46b | 996.9±97.51a |

| 根际K+ Rhizosphere K+ (mg/kg) |

20.59±3.42b | 343.59±34.86a |

| 叶际EC Phyllosphere EC (µs/cm) |

31.75±5.31b | 110.25±13.88a |

| 叶际Na+ Phyllosphere Na+ (mg/kg) |

20.07±4.22b | 162±19.34a |

| 叶际K+ Phyllosphere K+ (mg/kg) |

3.27±0.72b | 11.38±1.86a |

| SWC:土壤相对含水量;EC:电导率;不同小写字母表示组间差异显著 SWC: Soil water content; EC: Electrical conductivity; Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between groups. |

||

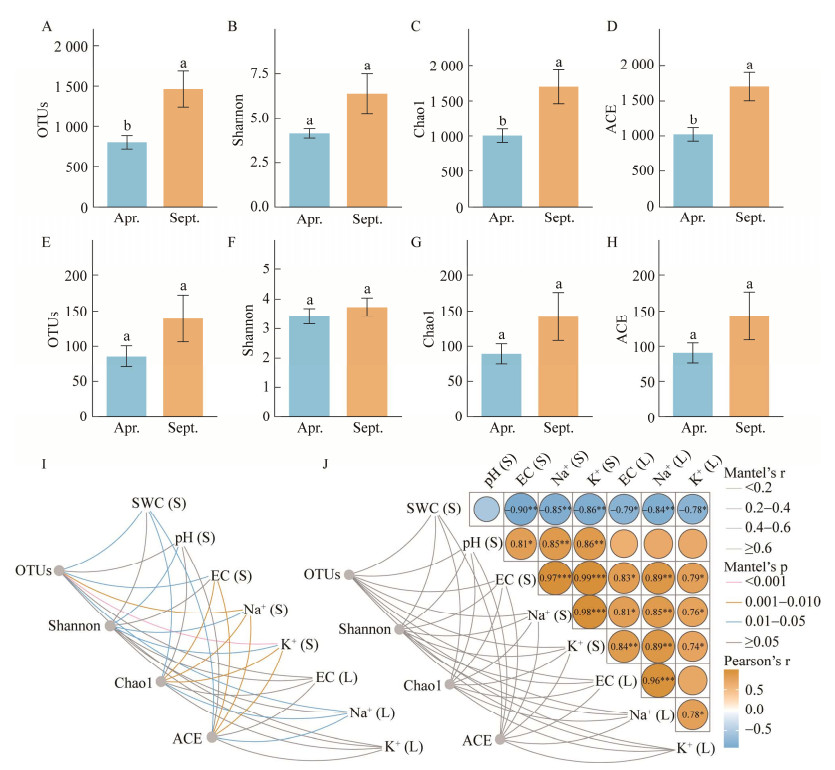

高通量测序获得715 878 (细菌)和811 392 (真菌)高质量读数(reads)。每个样本归一化后reads分别为41 739 (细菌)和60 239 (真菌),按照97%的序列相似性阈值分为3 343 (细菌)和544 (真菌)个OTU。如图 2A−2D所示,秋季长叶红砂叶际细菌OTU、Chao1和ACE指数均显著高于春季(P < 0.05),真菌的OTU、Chao1和ACE指数高于春季,但并不显著(图 2E−2H)。结合图 2可以看出,长叶红砂冠下土壤和叶片表面EC、Na+、K+存在显著正相关,并且与细菌OTU、Shannon、Chao1和ACE指数均存在较大相关性(图 2I),而与真菌α多样性的相关性并不明显(图 2J)。

|

| 图 2 细菌和真菌群落的α多样性指数分析及其与EC、Na+、K+含量的相关性 Figure 2 Analysis on the alpha diversity indices of phyllosphere and correlation between the alpha diversity index and EC, Na+ and K+ content. A−D:叶际细菌OTU数量、Shannon指数、Chao1指数和ACE指数. E−H:叶际真菌OTU数量、Shannon指数、Chao1指数和ACE指数. I:叶际细菌α多样性指数与土壤理化性质的相关性. J:叶际真菌α多样性指数与土壤理化性质的相关性以及土壤理化性质之间的相关性. *:P < 0.05;**:P < 0.01;***:P < 0.001. S:长叶红砂冠下土壤理化指标;L:长叶红砂叶片表面理化指标 A−D: OTU numbers, Shannon index, Chao1 index and ACE index of phyllosphere bacteria. E−H: OTU numbers, Shannon index, Chao1 index and ACE index of phyllosphere fungi. I: Correlation between alpha diversity index of phyllosphere bacteria and soil physicochemical properties. J: Correlation between alpha diversity index of phyllosphere fungi and soil physicochemical properties. *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001. Apr.: April; Sept.: September. S: Crown of soil; L: Leaf surface of Reaumuria trigyna. |

|

|

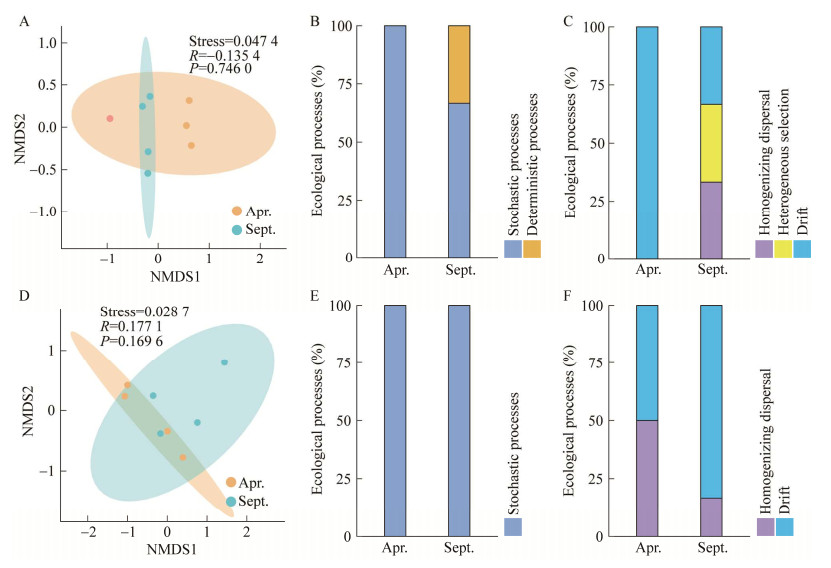

基于Bray-Curtis距离对长叶红砂细菌和真菌的β多样性进行分析,由图 3可以看出,春季和秋季长叶红砂的细菌群落组内差异大于组间差异(R=−0.135 4,P=0.746) (图 3A)。进一步对长叶红砂叶际细菌的群落构建过程进行分析,结果表明,叶际细菌群落的构建在春季全部由随机过程主导,而在秋季随机过程占66.67%,确定性过程占33.33%。从更低水平的生态过程分析来看,在春季,叶际细菌的生态漂变占群落变异的100%;而在秋季,叶际细菌的均质扩散、异质选择和生态漂变均占群落变异的33.33% (图 3B、3C)。真菌群落的组成存在组间差异性(R=0.177 1,P=0.169 6),但细菌和真菌的群落组成差异均不显著(P > 0.05) (图 3D)。然而叶际真菌群落的构建在春季和秋季均由随机过程主导,同样从更低水平的生态过程分析来看,春季叶际真菌的均质扩散和生态漂变各占群落变异的50%;秋季叶际真菌的均质扩散和生态漂变分别占群落变异的83.33%和16.67% (图 3E、3F)。

|

| 图 3 叶际细菌和真菌非度量多维尺度分析以及群落构建过程 Figure 3 Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination analysis of phyllosphere bacteria and fungi and community construction process. A:叶际细菌的非度量多维尺度分析. B:叶际细菌的群落构建过程. C:叶际细菌的不同生态过程. D:叶际真菌的非度量多维尺度分析. E:叶际真菌的群落构建过程. F:叶际真菌不同生态过程 A: NMDS analysis of phyllosphere bacteria. B: Community construction process of phyllosphere bacteria. C: Different ecological processes of phyllosphere bacteria. D: NMDS analysis of phyllosphere fungi. E: Community construction process of phyllosphere fungi. F: Different ecological processes of phyllosphere fungi. |

|

|

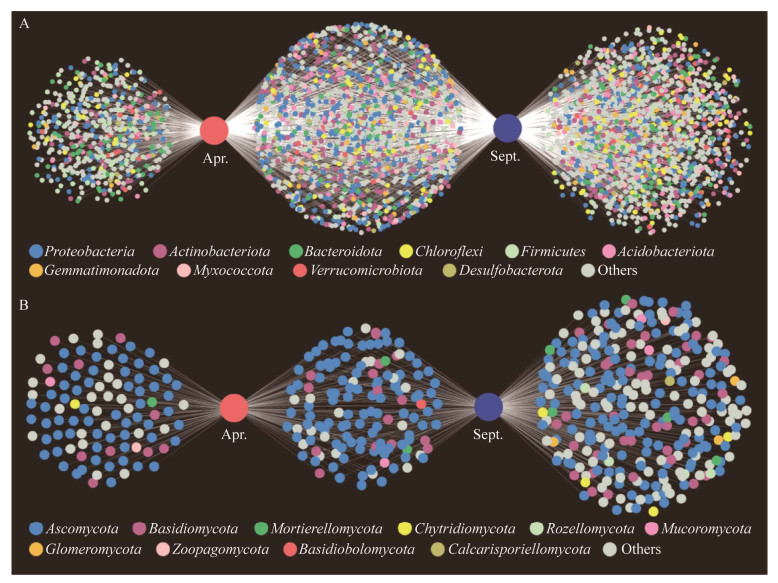

在相似性为97%的水平上,长叶红砂叶际中检测的OTU可以划分为68个细菌门类和16个真菌门类。如图 4所示,春季和秋季长叶红砂叶际细菌共有1 411个OTU,春季独有502个OTU,秋季独有1 430个OTU;春季和秋季长叶红砂叶际真菌共有OTU为139个,春季独有102个OTU,秋季独有303个OTU。

|

| 图 4 叶际细菌(A)和真菌(B) OTU关系分析 Figure 4 Analysis on the OTUs relationship of phyllosphere bacteria (A) and fungi (B). |

|

|

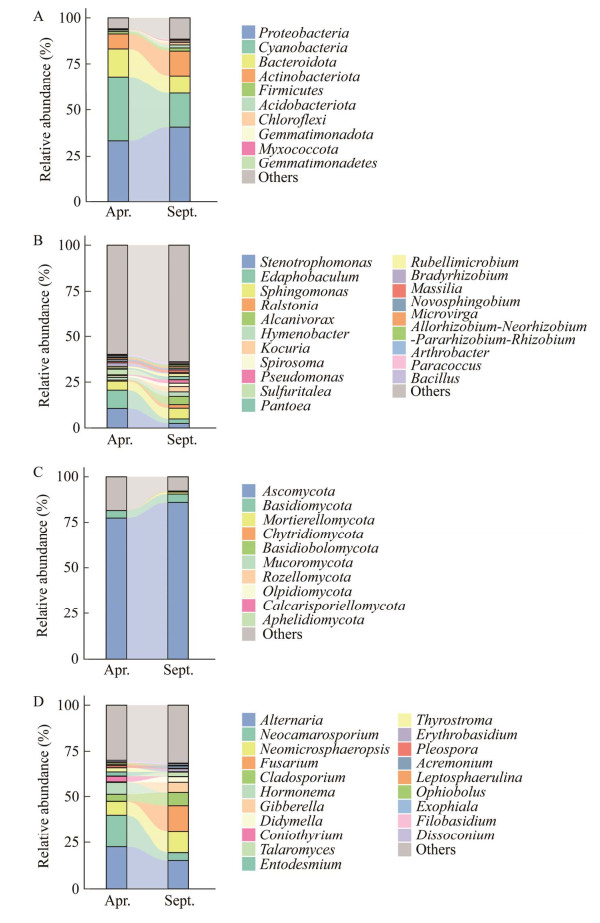

如图 5A所示,红砂叶际细菌主要由变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、蓝细菌门(Cyanobacteria)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidota)、放线菌门(Actinobacteriota)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteriota)、绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi)、粘细菌门(Myxococcota)和芽单胞菌门(Gemmatimonadota)组成。随着季节的变化,细菌中变形菌门(33.37%−40.63%)、蓝细菌门(38.44%−18.28%)、拟杆菌门(11.61%−9.52%)和放线菌门(7.09%−13.53%)是长叶红砂叶际在两个季节变化较大的菌门(图 5A)。细菌群落在属水平上共获得654个细菌属,与春季相比,秋季寡养单胞菌属(Stenotrophomonas) (8.33%−2.36%)、Edaphobaculum菌属(7.5%−2.5%)和罗尔斯顿菌属(Ralstonia) (4.78%−1.93%)的相对丰度降低,而鞘氨醇单胞菌属(Sphingomonas) (3.79%−5.87%)、Alcanivorax菌属(0.02%−4.54%)、薄层菌属(Hymenobacter) (1.1%−2.42%)和考克氏菌属(Kocuria) (0.06%−2.93%)的相对丰度升高(图 5B)。

|

| 图 5 叶际细菌和真菌群落组成 Figure 5 Community composition of phyllosphere bacteria and fungi. A:叶际细菌门水平上的群落组成. B:叶际细菌属水平上的群落组成. C:叶际真菌门水平上的群落组成. D:叶际真菌属水平上的群落组成 A: Community composition at the phylum level of phyllosphere bacteria. B: Genus level of phyllosphere bacteria. C: Community composition at the phylum level of phyllosphere fungi. D: Genus level of phyllosphere fungi. |

|

|

长叶红砂叶际真菌中主要菌门是子囊菌门(Ascomycota)、担子菌门(Basidiomycota)、被孢霉门(Mortierellomycota)、壶菌门(Chytridiomycota)、蛙粪菌门(Basidiobolomycota)、毛霉菌门(Mucoromycota)、罗兹菌门(Rozellomycota)、油壶菌门(Olpidiomycota)、虫霉菌门(Calcarisporiellomycota)和Aphelidiomycota菌门(图 5C)。子囊菌门(77.44%−85.98%)在秋季的相对丰度占比较高。在333个真菌菌属中,秋季链格孢菌属(Alternaria) (22.52%−15.1%)、新凸轮孢菌属(Neocamarosporium) (17.32%−4.25%)和Hormonema菌属(6.39%−0)相对丰度降低,而Neomicrosphaeropsis菌属(7.54%−11.73%)、镰刀菌属(Fusarium) (0.1%−13.95%)、分枝孢子菌属(Cladosporium) (3.76%−7.19%)、赤霉菌属(Gibberella) (0.03%−5.54%)和亚隔孢壳菌属(Didymella) (0.35%−3.02%)的相对丰度升高(图 5D)。

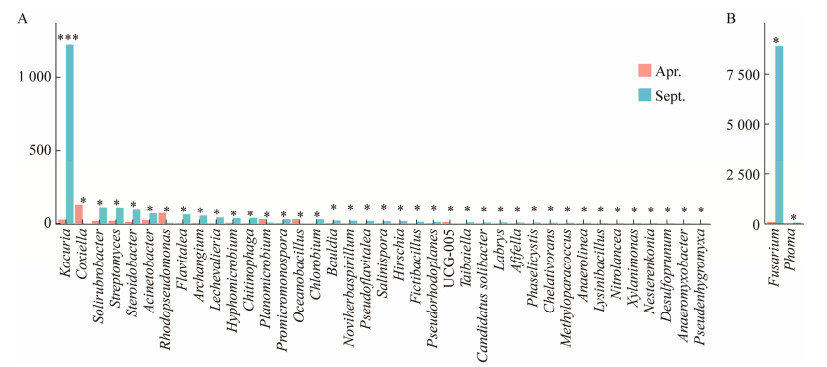

长叶红砂叶际细菌的差异菌属有39个,其中极显著差异的菌属为考克氏菌属(Kocuria);叶际真菌的差异菌属有2个,分别为镰刀菌属(Fusarium)和茎点霉属(Phoma) (图 6)。

|

| 图 6 叶际细菌(A)和真菌(B)的差异菌属分析. Figure 6 Analysis on different genera of phyllosphere bacteria (A) and fungi (B). *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001. |

|

|

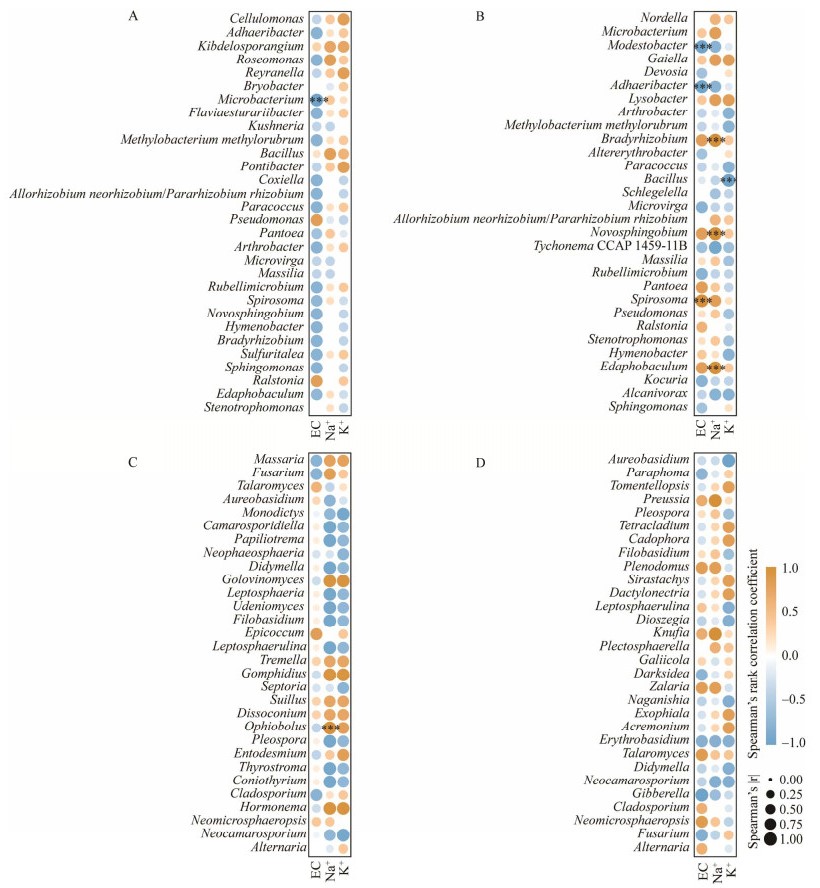

根据叶面EC、Na+、K+含量及叶际细菌、真菌菌属进行相关性分析,由图 7A可见,微杆菌属(Microbacterium)在春季与叶面EC呈显著负相关(P < 0.001)。秋季时,贫养杆菌属(Modestobacter)、阿达尔杆菌属(Adhaeribacter)、芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus)和叶面EC呈显著负相关,而螺状菌属(Spirosoma)则与EC呈正相关;慢生根瘤菌属(Bradyrhizobium)和新鞘脂菌属(Novosphingobium)与叶片Na+含量具有正相关性(图 7B);芽孢杆菌属与叶片K+含量是负相关关系。叶际真菌中,只有蛇孢腔菌属(Ophiobolus)在春季与叶片表面Na+具有显著的正相关关系(图 7C)。

|

| 图 7 叶际细菌和真菌与EC、Na+、K+含量的相关性 Figure 7 Correlation analysis on the between phyllosphere bacteria and fungi with EC, Na+, K+ content. A:春季长叶红砂叶际细菌与EC、Na+、K+含量相关性分析. B:秋季长叶红砂叶际细菌与EC、Na+、K+含量相关性分析. C:春季长叶红砂叶际真菌与EC、Na+、K+含量相关性分析. D:秋季长叶红砂叶际真菌与EC、Na+、K+含量相关性分析 A: Correlation analysis on the phyllosphere bacteria with EC, Na+, K+ content on April. B: Phyllosphere bacteria with EC, Na+, K+ content on September. C: Phyllosphere fungi with EC, Na+, K+ content on April. D: Phyllosphere fungi with EC, Na+, K+ content on September. *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001. |

|

|

荒漠草原地下水的渗入和季节性降水是其主要水源,气温升高、季节更替导致土壤水分蒸发大于降水量时,土壤盐分随水分向地表迁移[36-37]。本研究中,随着季节更替,长叶红砂秋季根际土壤含水率低于春季,土壤电导率指数呈上升趋势。大量研究表明,干旱加剧了荒漠草原土壤盐渍化,长叶红砂作为泌盐盐生植物,可以通过盐腺在叶片表面分泌过多的盐分来抵御盐胁迫[38-39]。我们研究发现,随着长叶红砂根际土壤EC指数上升,叶际EC也随之升高,其中秋季Na+和K+含量均显著高于春季[40]。Mi等在泌盐盐生植物补血草属(Limonium)植物的研究中指出,盐腺Na+含量和速率与盐浓度呈正相关[38],我们的研究得到了相似的结果。

较多研究认为,植物叶际微生物群落多样性受季节变化的影响[41-43]。我们的研究中,长叶红砂叶际细菌和真菌α多样性指数在春季和秋季存在差异;与此同时,长叶红砂秋季叶际细菌和真菌OTUs、ACE和Chao1指数高于春季。已有研究表明,植物叶际微生物群落多样性的时间/季节变化受温度、湿度和太阳辐射等非生物因素的驱动[20-21]。此外,风雨等随机天气事件的出现,直接影响了叶表面微生物的选择性生长和定殖[14, 44]。我们研究发现,植物叶际细菌群落的组成不仅受季节变化的影响,同时也是叶际环境变化的结果[45-47]。Finkel等针对泌盐盐生植物柽柳的研究中指出,植物叶际渗出物成分、水分有效性、盐度、pH等条件均是决定微生物在叶际定殖的因素[48]。本研究中,长叶红砂叶际泌盐对细菌和真菌群落多样性产生较大影响,进一步说明植物叶际盐分积累对微生物群落的组成具有较大影响。

细菌被认为是叶际中最丰富的类群,最常见的叶际细菌群通常包括变形菌门、拟杆菌门、厚壁菌门和放线菌门[25, 49-51]。本研究中,长叶红砂叶际细菌主要由变形菌门、蓝细菌门、拟杆菌门、放线菌门和厚壁菌门组成,这与前人在拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)、银杏、白皮松和杉木的研究结果相似[14]。Redford等对三角杨(Populus deltoids)生长季叶际微生物群落变化的研究中发现,植物在生长的早期和后期,其叶际微生物群落组成主要是变形菌门,而叶际微生物群落的差异主要以放线菌门为主[22]。本研究中,长叶红砂叶际变形菌门、蓝细菌门和放线菌门的相对丰度在季节更替下均呈现不同程度的变化。此外,长叶红砂叶际真菌主要由子囊菌门和担子菌门构成,这与之前的研究结果[52-54]相一致。属水平上,链格孢菌具有较大的占比,已有的研究也发现链格孢菌成员是植物叶际的主要成员[55]。分枝孢子菌作为主要的空气真菌成员,在夏秋季具有较高的相对丰度占比和强烈的季节效应,同时对植物的适应性产生有益影响[53, 56]。本研究中,长叶红砂秋季叶际分枝孢子菌属相对丰度占比增加,与前人的研究结果相似。

叶际微生物固氮是植物氮营养获取的方式之一,早期的研究指出蓝细菌门的很多成员具有固定大气氮的功能[57-60]。本研究中,蓝细菌门受叶际盐分的影响相对丰度占比降低。除了氮,叶际微生物还通过溶解特性促进植物磷营养的获取,如芽孢杆菌属、假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas)的部分成员[61-63]。本研究中,微杆菌属和芽孢杆菌属与叶际盐分的积累呈现显著负相关关系,可以推测,长叶红砂叶际盐分的积累降低了营养获取微生物的相对丰度,进而对植物氮磷等营养的获取造成不利影响[12]。此外,叶际微生物通过产生VOCs诱导宿主免疫系统,提高植物抵抗病原体入侵的能力[64]。长叶红砂叶际寡养单胞菌属的相对丰度占比随季节更替明显减低,该菌属已被证明是植物叶际的促生菌,通过产生VOCs抑制病原体生长[65]。更多研究表明,烷烃降解菌(Alcanivorax)成员具有生物表面活性剂的生产、分解和聚集特性;假单胞菌成员具有鞭毛,也具有产生生物表面活性剂的功能[66-67]。本研究中,烷烃降解菌属和假单胞菌属相对丰度占比随季节更替随之增加,这或许是长叶红砂秋季叶际微生物丰富度增加的原因,也是微生物-植物相互作用保护植物免受胁迫侵害的重要原因[68-69]。

植物叶际是与大气直接接触的开放表面,鉴于紫外辐射对叶际微生物群落的干扰,假单胞菌成员还具有蓝光受体蛋白[70]。我们研究发现,该菌属在秋季相对丰度占比增加,有助于长叶红砂抵御紫外辐射[70]。此外,烷烃降解菌和新凸轮孢菌属于嗜盐菌,在长叶红砂叶际中具有较大的相对丰度占比;已有研究表明,新凸轮孢菌属与海洋或盐碱生境中的盐生植物有联系,通常可在盐水、高盐土壤等含盐环境中发现[54, 71-73]。现有研究已证实,蛇孢腔菌属大部分成员是欧洲和北美草本植物上的病原菌[74]。本研究中,蛇孢腔菌属与叶际盐分含量呈显著正相关,表明长叶红砂叶际泌盐增加了病原菌定殖的机会。另外,Edaphobaculum菌属的相对丰度占比随季节更替明显减低,近期的一项研究发现,该菌属成员分离自内蒙古草原土壤,这也进一步证实叶际微生物群落和土壤微生物群落具有一定相关性[75]。

综上所述,植物叶际是一种奇特的微生物栖息地,在植物生长和发育过程中发挥着多种多样的功能。利用细菌16S rRNA基因和真菌ITS区域进行分子表征,可以有效揭示叶际微生物群落的多样性[1, 3]。虽然影响微生物群落构建的因素现在已很好理解,但我们的理解仅限于某些微生物群体,对于微生物个体间相互作用的认识仍然需要进一步探索。本研究为理解植物叶际微生物群落响应盐分积累等方面的研究提供了一定的科学依据,今后的研究应结合植物根际生境、植物叶际泌盐动态进行全面分析。

| [1] |

LINDOW SE, BRANDL MT, LINDOW SE, BRANDL MT. Microbiology of the phyllosphere[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(4): 1875-1883. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.4.1875-1883.2003 |

| [2] |

KNIEF C, FRANCES L, VORHOLT JA. Competitiveness of diverse Methylobacterium strains in the phyllosphere of Arabidopsis thaliana and identification of representative models, including M. extorquens PA1[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2010, 60(2): 440-452. DOI:10.1007/s00248-010-9725-3 |

| [3] |

VORHOLT JA. Microbial life in the phyllosphere[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2012, 10(12): 828-840. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2910 |

| [4] |

VANDENKOORNHUYSE P, QUAISER A, DUHAMEL M, van AL, Dufresne A. The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont[J]. New Phytologist, 2015, 206(4): 1196-1206. DOI:10.1111/nph.13312 |

| [5] |

HELFRICH EJN, VOGEL CM, UEOKA R, SCHÄFER M, RYFFEL F, MÜLLER DB, PROBST S, KREUZER M, PIEL J, VORHOLT JA. Bipartite interactions, antibiotic production and biosynthetic potential of the Arabidopsis leaf microbiome[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2018, 3(8): 909-919. DOI:10.1038/s41564-018-0200-0 |

| [6] |

YANG K, WANG HL, YE KH, WANG P, MENG GY, LUO C, GUO LW. Advances in research on phyllosphere microorganisms and their interaction with plants[J]. Journal of Yunnan Agricultural University (Natural Science), 2021, 36(1): 155-164. (in Chinese) 杨宽, 王慧玲, 叶坤浩, 王佩, 孟广云, 罗成, 郭力维. 叶际微生物及与植物互作的研究进展[J]. 云南农业大学学报(自然科学版), 2021, 36(1): 155-164. |

| [7] |

SPAEPEN S, VANDERLEYDEN J, REMANS R. Indole-3-acetic acid in microbial and microorganism- plant signaling[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2007, 31(4): 425-448. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00072.x |

| [8] |

VENKATACHALAM S, RANJAN K, PRASANNA R, RAMAKRISHNAN B, THAPA S, KANCHAN A. Diversity and functional traits of culturable microbiome members, including cyanobacteria in the rice phyllosphere[J]. Plant Biology, 2016, 18(4): 627-637. DOI:10.1111/plb.12441 |

| [9] |

THAPA S, RANJAN K, RAMAKRISHNAN B, VELMOUROUGANE K, PRASANNA R. Influence of fertilizers and rice cultivation methods on the abundance and diversity of phyllosphere microbiome[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2018, 58(2): 172-186. DOI:10.1002/jobm.201700402 |

| [10] |

DAR GH, BHAT RA, MEHMOOD MA, HAKEEM KR. Microbiota and Biofertilizers, Vol 2: Ecofriendly Tools for Reclamation of Degraded Soil Environs[M]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

|

| [11] |

STANTON DE, BATTERMAN SA, von FISCHER JC, HEDIN LO. Rapid nitrogen fixation by canopy microbiome in tropical forest determined by both phosphorus and molybdenum[J]. Ecology, 2019, 100(9): e02795. |

| [12] |

ABADI VAJM, SEPEHRI M, RAHMANI HA, ZAREI M, RONAGHI A, TAGHAVI SM, SHAMSHIRIPOUR M. Role of dominant phyllosphere bacteria with plant growth-promoting characteristics on growth and nutrition of maize (Zea mays L.)[J]. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 2020, 20(4): 2348-2363. DOI:10.1007/s42729-020-00302-1 |

| [13] |

QIAN X, LI SC, WU BW, WANG YL, JI NN, YAO H, CAI HY, SHI MM, ZHANG DX. Mainland and island populations of Mussaenda kwangtungensis differ in their phyllosphere fungal community composition and network structure[J]. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10: 952-966. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-57622-6 |

| [14] |

BAO LJ, GU LK, SUN B, CAI WY, ZHANG SW, ZHUANG GQ, BAI ZH, ZHUANG XL. Seasonal variation of epiphytic bacteria in the phyllosphere of Gingko biloba, Pinus bungeana and Sabina chinensis[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2020, 96(3): fiaa017. DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiaa017 |

| [15] |

GAO S, LIU XC, DONG Z, LIU MY, DAI LY. Advance of phyllosphere microorganisms and their interaction with the outside environment[J]. Plant Science Journal, 2016, 34(4): 654-661. (in Chinese) 高爽, 刘笑尘, 董铮, 刘茂炎, 戴良英. 叶际微生物及其与外界互作的研究进展[J]. 植物科学学报, 2016, 34(4): 654-661. |

| [16] |

RASTOGI G, SBODIO A, TECH JJ, SUSLOW TV, COAKER GL, LEVEAU JHJ. Leaf microbiota in an agroecosystem: spatiotemporal variation in bacterial community composition on field-grown lettuce[J]. The ISME Journal, 2012, 6(10): 1812-1822. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2012.32 |

| [17] |

CORDIER T, ROBIN C, CAPDEVIELLE X, DESPREZ-LOUSTAU ML, VACHER C. Spatial variability of phyllosphere fungal assemblages: genetic distance predominates over geographic distance in a European beech stand (Fagus sylvatica)[J]. Fungal Ecology, 2012, 5(5): 509-520. DOI:10.1016/j.funeco.2011.12.004 |

| [18] |

PEÑUELAS J, RICO L, OGAYA R, JUMP AS, TERRADAS J. Summer season and long-term drought increase the richness of bacteria and fungi in the foliar phyllosphere of Quercus ilex in a mixed Mediterranean forest[J]. Plant Biology: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012, 14(4): 565-575. DOI:10.1111/j.1438-8677.2011.00532.x |

| [19] |

MATERATSKI P, VARANDA C, CARVALHO T, DIAS AB, CAMPOS MD, REI F, FÉLIX MDR. Spatial and temporal variation of fungal endophytic richness and diversity associated to the phyllosphere of olive cultivars[J]. Fungal Biology, 2019, 123(1): 66-76. DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2018.11.004 |

| [20] |

BEATTIE GA. Water relations in the interaction of foliar bacterial pathogens with plants[J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2011, 49: 533-555. DOI:10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114436 |

| [21] |

JOUNG YS, GE ZF, BUIE CR. Bioaerosol generation by raindrops on soil[J]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8: 14668. DOI:10.1038/ncomms14668 |

| [22] |

REDFORD AJ, FIERER N. Bacterial succession on the leaf surface: a novel system for studying successional dynamics[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2009, 58(1): 189-198. DOI:10.1007/s00248-009-9495-y |

| [23] |

IBEKWE AM, ORS S, FERREIRA JFS, LIU X, SUAREZ DL. Influence of seasonal changes and salinity on spinach phyllosphere bacterial functional assemblage[J]. PLoS One, 2021, 16(6): e0252242. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0252242 |

| [24] |

KIM M, SINGH D, LAI-HOE A, GO R, RAHIM RA, AINUDDIN AN, CHUN J, ADAMS JM. Distinctive phyllosphere bacterial communities in tropical trees[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 63(3): 674-681. DOI:10.1007/s00248-011-9953-1 |

| [25] |

KEMBEL SW, O՚CONNOR TK, ARNOLD HK, HUBBELL SP, WRIGHT SJ, GREEN JL. Relationships between phyllosphere bacterial communities and plant functional traits in a neotropical forest[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(38): 13715-13720. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1216057111 |

| [26] |

KEMBEL SW, MUELLER RC. Plant traits and taxonomy drive host associations in tropical phyllosphere fungal communities[J]. Botany, 2014, 92(4): 303-311. DOI:10.1139/cjb-2013-0194 |

| [27] |

LIU RX, JIN K, MA YM, CHEN SC, MI YJ. Study on salt secretion characteristics of Reaumuria soongorica in Ejina desert[J]. Chinese Journal of Grassland, 2021, 43(5): 75-81. (in Chinese) 刘瑞香, 靳凯, 马迎梅, 陈士超, 米艳杰. 额济纳荒漠红砂泌盐特征的研究[J]. 中国草地学报, 2021, 43(5): 75-81. |

| [28] |

XUE Y, WANG YC. Study on characters of ions secretion from Reaumuria trigyna[J]. Journal of Desert Research, 2008(3): 437-442, 602. (in Chinese) 薛焱, 王迎春. 盐生植物长叶红砂泌盐特性的研究[J]. 中国沙漠, 2008(3): 437-442, 602. |

| [29] |

PAN YQ, GUO H, WANG SM, ZHAO BY, ZHANG JL, MA Q, YIN HJ, BAO AK. The photosynthesis, Na+/K+ homeostasis and osmotic adjustment of Atriplex canescens in response to salinity[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2016, 7: 848. |

| [30] |

WUJISIGULENG, KANG P, HU JP, PAN YQ, ZHOU Y, MA R, PENG YY, LIU JL. Difference in endophyte community structure between young and mature branches of Artemisia ordosica[J]. Microbiology China, 2022, 49(2): 569-582. (in Chinese) 乌吉斯古冷, 康鹏, 胡金鹏, 潘雅清, 周月, 马蓉, 彭伊扬, 刘建利. 荒漠植物黑沙蒿嫩枝与成熟枝内生菌群落结构差异[J]. 微生物学通报, 2022, 49(2): 569-582. |

| [31] |

EDGAR RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads[J]. Nature Methods, 2013, 10(10): 996-998. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.2604 |

| [32] |

KANG P, PAN YQ, YANG P, HU JP, ZHAO TL, ZHANG YQ, DING XD, YAN XF. A comparison of microbial composition under three tree ecosystems using the stochastic process and network complexity approaches[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022, 13: 101877. |

| [33] |

ZIEGLER M, SENECA FO, YUM LK, PALUMBI SR, VOOLSTRA CR. Bacterial community dynamics are linked to patterns of coral heat tolerance[J]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8: 14213. DOI:10.1038/ncomms14213 |

| [34] |

PAN YQ, KANG P, HU JP, SONG NP. Bacterial community demonstrates stronger network connectivity than fungal community in desert-grassland salt marsh[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 798: 149118. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149118 |

| [35] |

NING DL, YUAN MT, WU LW, ZHANG Y, GUO X, ZHOU XS, YANG YF, ARKIN AP, FIRESTONE MK, ZHOU JZ. A quantitative framework reveals ecological drivers of grassland microbial community assembly in response to warming[J]. Nature Communications, 2020, 11: 4717. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-18560-z |

| [36] |

LIU M, LIU GH, WU X, WANG H, CHEN L. Vegetation traits and soil properties in response to utilization patterns of grassland in Hulun Buir city, Inner Mongolia, China[J]. Chinese Geographical Science, 2014, 24(4): 471-478. DOI:10.1007/s11769-014-0706-1 |

| [37] |

ZHANG NL, WAN SQ, GUO JX, HAN GD, GUTKNECHT J, SCHMID B, YU L, LIU WX, BI J, WANG Z, MA KP. Precipitation modifies the effects of warming and nitrogen addition on soil microbial communities in northern Chinese grasslands[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2015, 89: 12-23. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.06.022 |

| [38] |

MI P, YUAN F, GUO J, HAN G, WANG B. Salt glands play a pivotal role in the salt resistance of four recretohalophyte Limonium Mill. species[J]. Plant Biology: Stuttgart, Germany, 2021, 23(6): 1063-1073. DOI:10.1111/plb.13284 |

| [39] |

DU C, MA BJ, WU ZG, LI NN, ZHENG LL, WANG YC. Reaumuria trigyna transcription factor RtWRKY23 enhances salt stress tolerance and delays flowering in plants[J]. Journal of Plant Physiology, 2019, 239: 38-51. DOI:10.1016/j.jplph.2019.05.012 |

| [40] |

XUE Y, WANG YC, WANG TZ. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of an endemic halophyte Reaumuria trigyna Maxim. under salt stress[J]. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica, 2012, 32(1): 136-142. (in Chinese) 薛焱, 王迎春, 王同智. 濒危植物长叶红砂适应盐胁迫的生理生化机制研究[J]. 西北植物学报, 2012, 32(1): 136-142. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-4025.2012.01.022 |

| [41] |

STONE B, Weingarten E. The role of the phyllosphere microbiome in plant health and function[J]. Annual Plant Reviews, 2018, 1(2): 53. |

| [42] |

DIAS NS, FERREIRA JFS, LIU X, SUAREZ DL. Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) maintains high inulin, tuber yield, and antioxidant capacity under moderately-saline irrigation waters[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2016, 94: 1009-1024. DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.09.029 |

| [43] |

GURON GKP, ARANGO-ARGOTY G, ZHANG LQ, PRUDEN A, PONDER MA. Effects of dairy manure-based amendments and soil texture on lettuce- and radish-associated microbiota and resistomes[J]. mSphere, 2019, 4(3): e00239-e00219. |

| [44] |

ANDREWS JH, HARRIS RF. The ecology and biogeography of microorganisms on plant surfaces[J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2000, 38: 145-180. DOI:10.1146/annurev.phyto.38.1.145 |

| [45] |

WILLIAMS TR, MOYNE AL, HARRIS LJ, MARCO ML. Season, irrigation, leaf age, and Escherichia coli inoculation influence the bacterial diversity in the lettuce phyllosphere[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e68642. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0068642 |

| [46] |

MARK IBEKWE A, ORS S, FERREIRA JFS, LIU X, SUAREZ DL. Seasonal induced changes in spinach rhizosphere microbial community structure with varying salinity and drought[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 579: 1485-1495. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.151 |

| [47] |

FROELICH BA, WILLIAMS TC, NOBLE RT, OLIVER JD. Apparent loss of Vibrio vulnificus from north Carolina oysters coincides with a drought-induced increase in salinity[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(11): 3885-3889. DOI:10.1128/AEM.07855-11 |

| [48] |

FINKEL OM, DELMONT TO, POST AF, BELKIN S. Metagenomic signatures of bacterial adaptation to life in the phyllosphere of a salt-secreting desert tree[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(9): 2854-2861. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00483-16 |

| [49] |

REISBERG EE, HILDEBRANDT U, RIEDERER M, HENTSCHEL U. Distinct phyllosphere bacterial communities on Arabidopsis wax mutant leaves[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(11): e78613. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0078613 |

| [50] |

DURAND A, MAILLARD F, ALVAREZ-LOPEZ V, GUINCHARD S, BERTHEAU C, VALOT B, BLAUDEZ D, CHALOT M. Bacterial diversity associated with poplar trees grown on a Hg-contaminated site: community characterization and isolation of Hg-resistant plant growth-promoting bacteria[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 622/623: 1165-1177. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.069 |

| [51] |

CARVALHO CR, DIAS AC, HOMMA SK, CARDOSO EJ. Phyllosphere bacterial assembly in citrus crop under conventional and ecological management[J]. PeerJ, 2020, 8: e9152. DOI:10.7717/peerj.9152 |

| [52] |

SUN H, LI H, ZHAN YG, LI Y. Phyllosphere bacterial community structure of Osmanthus fragrans and Nerium indicum in different habitats[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2018, 29(5): 1653-1659. (in Chinese) 孙泓, 李慧, 詹亚光, 李杨. 不同生境中桂花和夹竹桃叶际细菌的群落结构[J]. 应用生态学报, 2018, 29(5): 1653-1659. |

| [53] |

KATSOULA A, VASILEIADIS S, KARAMANOLI K, VOKOU D, KARPOUZAS DG. Factors structuring the epiphytic archaeal and fungal communities in a semi-arid Mediterranean ecosystem[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2021, 82(3): 638-651. DOI:10.1007/s00248-021-01712-z |

| [54] |

XING L, YANG JL, JIA YH, HU X, LIU Y, XU H, YIN HQ, LI J, YI ZX. Effects of ecological environment and host genotype on the phyllosphere bacterial communities of cigar tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.)[J]. Ecology and Evolution, 2021, 11(16): 10892-10903. DOI:10.1002/ece3.7861 |

| [55] |

MÜLLER T, BEHRENDT U, RUPPEL S, von der WAYDBRINK G, MÜLLER MEH. Fluorescent pseudomonads in the phyllosphere of wheat: potential antagonists against fungal phytopathogens[J]. Current Microbiology, 2016, 72(4): 383-389. DOI:10.1007/s00284-015-0966-8 |

| [56] |

QIN Y, PAN XY, YUAN ZL. Seed endophytic microbiota in a coastal plant and phytobeneficial properties of the fungus Cladosporium cladosporioides[J]. Fungal Ecology, 2016, 24: 53-60. DOI:10.1016/j.funeco.2016.08.011 |

| [57] |

SHA XL, LIANG SX, ZHUANG XL, HAN QL, BAI ZH. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the phyllosphere[J]. Microbiology China, 2017, 44(10): 2443-2451. (in Chinese) 沙小玲, 梁胜贤, 庄绪亮, 韩庆莉, 白志辉. 植物叶际固氮菌研究进展[J]. 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(10): 2443-2451. |

| [58] |

ABRIL AB, TORRES PA, BUCHER EH. The importance of phyllosphere microbial populations in nitrogen cycling in the Chaco semi-arid woodland[J]. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 2005, 21(1): 103-107. DOI:10.1017/S0266467404001981 |

| [59] |

BENTLEY BL. Nitrogen fixation by epiphylls in a tropical rainforest[J]. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 1987, 74(2): 234. DOI:10.2307/2399396 |

| [60] |

FREIBERG E. Microclimatic parameters influencing nitrogen fixation in the phyllosphere in a Costa Rican premontane rain forest[J]. Oecologia, 1998, 117(1): 9-18. |

| [61] |

KUMAR V, SINGH P, JORQUERA MA, SANGWAN P, KUMAR P, VERMA AK, AGRAWAL S. Isolation of phytase-producing bacteria from Himalayan soils and their effect on growth and phosphorus uptake of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea)[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2013, 29(8): 1361-1369. DOI:10.1007/s11274-013-1299-z |

| [62] |

VERMA P, YADAV A, KAZY S. Evaluating the diversity and phylogeny of plant growth promoting bacteria associated with wheat (Triticum aestivum) growing in central zone of India[J]. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 2014, 3(5): 432-447. |

| [63] |

de SOUZA R, BENEDUZI A, AMBROSINI A, da COSTA PB, MEYER J, VARGAS LK, SCHOENFELD R, PASSAGLIA LMP. The effect of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on the growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cropped in southern Brazilian fields[J]. Plant and Soil, 2013, 366(1): 585-603. |

| [64] |

WANG Y, LIU C, GAO J, LIU ZQ, WANG GX. Mechanism and application prospects of plant stomatal immunity induced by phyllosphere microbes[J]. Chinese Bulletin of Botany, 2013, 48(6): 658-664. (in Chinese) 王洋, 刘超, 高静, 刘志强, 王根轩. 叶际微生物诱发气孔免疫的机制及其应用前景[J]. 植物学报, 2013, 48(6): 658-664. |

| [65] |

ORTEGA RA, MAHNERT A, BERG C, MÜLLER H, BERG G. The plant is crucial: specific composition and function of the phyllosphere microbiome of indoor ornamentals[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2016, 92(12): fiw173. DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiw173 |

| [66] |

OLIVERA NL, NIEVAS ML, LOZADA M, del PRADO G, DIONISI HM, SIÑERIZ F. Isolation and characterization of biosurfactant-producing Alcanivorax strains: hydrocarbon accession strategies and alkane hydroxylase gene analysis[J]. Research in Microbiology, 2009, 160(1): 19-26. DOI:10.1016/j.resmic.2008.09.011 |

| [67] |

DENG BQ, LI W, LU HJ, ZHU LZ. Film mulching reduces antibiotic resistance genes in the phyllosphere of lettuce[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences: China, 2022, 112: 121-128. DOI:10.1016/j.jes.2021.04.032 |

| [68] |

HIRANO SS, UPPER CD. Bacteria in the leaf ecosystem with emphasis on Pseudomonas syringae—a pathogen, ice nucleus, and epiphyte[J]. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 2000, 64(3): 624-653. DOI:10.1128/MMBR.64.3.624-653.2000 |

| [69] |

SCHREIBER L, KRIMM U, KNOLL D. Interactions between epiphyllic microorganisms and leaf cuticles[A]//Plant Surface Microbiology[M]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004: 145-156.

|

| [70] |

ALSANIUS BW, VAAS L, GHARAIE S, KARLSSON ME, ROSBERG AK, WOHANKA W, KHALIL S, WINDSTAM S. Dining in blue light impairs the appetite of some leaf epiphytes[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2021, 12: 725021. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2021.725021 |

| [71] |

PAPIZADEH M, WIJAYAWARDENE NN, AMOOZEGAR MA, SABA F, FAZELI SAS, HYDE KD. Neocamarosporium jorjanensis, N. persepolisi, and N. solicola spp. nov. (Neocamarosporiaceae, Pleosporales) isolated from saline lakes of Iran indicate the possible halotolerant nature for the genus[J]. Mycological Progress, 2018, 17(5): 661-679. DOI:10.1007/s11557-017-1341-x |

| [72] |

GONÇALVES M. Three new species of Neocamarosporium isolated from saline environments: N. aestuarinum sp. nov., N. endophyticum sp. nov. and N. halimiones sp. nov[J]. Mycosphere, 2019, 10(1): 608-621. DOI:10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/11 |

| [73] |

BAATI H, AMDOUNI R, GHARSALLAH N, SGHIR A, AMMAR E. Isolation and characterization of moderately halophilic bacteria from Tunisian solar saltern[J]. Current Microbiology, 2010, 60(3): 157-161. DOI:10.1007/s00284-009-9516-6 |

| [74] |

PHOOKAMSAK R, WANASINGHE DN, HONGSANAN S, PHUKHAMSAKDA C, HUANG SK, TENNAKOON DS, NORPHANPHOUN C, CAMPORESI E, BULGAKOV TS, PROMPUTTHA I, MORTIMER PE, XU JC, HYDE KD. Towards a natural classification of Ophiobolus and Ophiobolus-like taxa; introducing three novel genera Ophiobolopsis, Paraophiobolus and Pseudoophiobolus in Phaeosphaeriaceae (Pleosporales)[J]. Fungal Diversity, 2017, 87(1): 299-339. DOI:10.1007/s13225-017-0393-1 |

| [75] |

CAO M, HUANG J, LI JX, QIAO ZX, WANG GJ. Edaphobaculum flavum gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of family Chitinophagaceae, isolated from grassland soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(11): 4475-4481. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002316 |

2023, Vol. 50

2023, Vol. 50