扩展功能

文章信息

- 南春利, 薛永常

- NAN Chunli, XUE Yongchang

- 顺式和反式-AT型聚酮合酶研究进展及应用

- Research progress and application of cis-AT and trans-AT polyketide synthase

- 微生物学通报, 2021, 48(11): 4377-4386

- Microbiology China, 2021, 48(11): 4377-4386

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.210178

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2021-02-19

- 接受日期: 2021-04-19

- 网络首发日期: 2021-05-09

聚酮类化合物是重要的微生物次生代谢物,是人类医药的重要来源之一,临床上常用的红霉素A和利福霉素S[1]、蒽环类的抗肿瘤药物多柔比星[2]、降低冠心病患者死亡率及致残率的降脂类药物洛伐他汀[3]、生物杀虫剂阿维菌素[4-5]等均来源于微生物产生的聚酮类化合物。聚酮类化合物结构多种多样,核心结构均由简单脂肪酸在聚酮合酶(Polyketide Synthase,PKS)催化下经过类似长链脂肪酸的合成途径生成,经过氧化、糖基化和甲基化后才能赋予代谢物生物活性;PKS根据结构及其性质可分成I型PKS (又称模件型)、II型PKS (又称迭代型)和Ⅲ型PKS (又称查尔酮型)三大类,放线菌中发现的主要是含有酰基转移酶域(Acyltransferase,AT)的I型PKS和II型PKS,其中又以I型PKS的研究最为透彻[6]。多烯大环内酯类抗生素均由I型PKS催化合成,如四霉素、菲律宾菌素、龟裂菌素等[7]。I型PKS进一步又可以分为顺式-AT (cis-Acyltransferase,cis-AT)型PKS和反式-AT (trans-Acyltransferase,trans-AT)型PKS,trans-AT型PKS也被称作AT-Less型PKS[8]。cis-AT型PKS的研究相对比较透彻,对于trans-AT型PKS研究较少,近期发现广泛存在于细菌群中的PKS约40%归属于trans-AT型PKS,其聚酮产物构成了主要类别的天然产物。

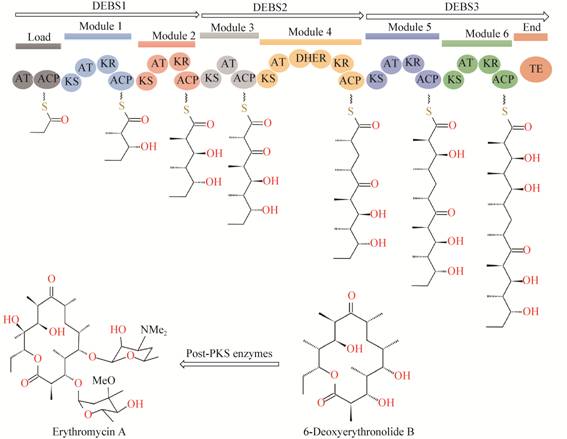

1 I型PKS的主要类型 1.1 cis-AT型和trans-AT型PKSI型PKS是一种大型多结构域酶复合物,每个模块专用于一轮链延伸及其特定中间体的后续加工,模块阵列就好比一条生产线,中间产物按顺序传递。在I型PKS模块中,聚酮化合物合成链延伸的单个周期所需的基本催化域包括用于单体选择的酰基转移酶(AT)、用于底物活化和穿梭的酰基载体蛋白(Acyl Carrier Protein,ACP),以及用于脱羧缩合的酮合酶(Ketoacylsynthase,KS)[9]。在聚酮链延伸之后,可以通过酮还原酶(Ketoreductase,KR)[10]、脱水酶(Dehydratase,DH)和烯醇还原酶(Enoylreductase,ER)等结构域对中间产物进行修饰。如负责红霉素A生物合成的PKS模块与产物有一一对应关系(图 1),这种共线性原理可帮助将每种产物分配给其合成酶[11-12]。cis-AT型PKS每个模块中都存在一个完整的AT域,其在I型PKS中占大部分;然而trans-AT型PKS是I型PKS的一种结构变体,其模块缺乏AT结构域,在每一个延伸步骤中AT活性是通过一个或几个独立的蛋白在聚酮生物合成基因簇内部或外部编码的[13-14]。trans-AT型PKS通常包含非规范模块和新的酶域,这导致在使用上述共线性规则时,基因簇的生物同步性分配较差[15]。trans-AT型PKS系统约占I型PKS的40%[16-17],代表了一个主要但特征不明确的酶类,与新型药物的发现密切相关。

|

| 图 1 红霉素A生物合成途径 Figure 1 Biosynthesis pathway of erythromycin A |

|

|

cis-AT型PKS和trans-AT型PKS是通过不同的机制进化而来。cis-AT型PKS由模块复制和域多样化指导为垂直机制进化,trans-AT型PKS由细菌间水平基因转移引导为水平机制进化[8]。

尽管cis-AT型PKS和trans-AT型PKS的进化起源不同,但它们都采用相同的生物同步原理来组装聚酮产品,在模块比较中二者最大的区别在于cis-AT域是集成的,而trans-AT域是离散的;此外,针对KS域而言,cis-AT型PKS的KS域系统发育分析表明它们具有很高的相似性,而trans-AT型PKS具有底物特异性,如来自Psymberin和Bacillaene途径的6个trans-AT型PKS的KS域的底物特异性表明PsyA-KS1天然底物是乙酰基链,尤其对2-氨基乙酰基绝对偏好,BaeJ-KS2和BaeL-KS5都倾向于含有较长酰基链的底物[18-19]。在聚酮合成过程中2种PKS存在一些修饰上的不同,如β-分支多存在于trans-AT型PKS路径中,少数存在于cis-AT型PKS路径[20]。甲基基团的添加cis-AT型PKS可以直接利用其AT域,而trans-AT型PKS则需要S-腺苷甲硫氨酸的辅助[8] (表 1)。

| Differences | cis-AT PKS | trans-AT PKS | Rerferences |

| 甲基 Methyl group |

AT将甲基基团添加到碳骨架上 AT adds methyl groups to the carbon framework |

甲基转移酶(Methyltransferase,MT) S-腺苷甲硫氨酸(SAM)衍生的甲基基团添加到碳骨架中 MT adds S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-derived methyl groups to the carbon framework |

[8] |

| 吡喃环 Pyran ring |

由DH结构域催化形成 Catalysed by DH |

由吡喃合成酶(Pyran synthase,PS)催化形成 Catalysed by PS |

[17] |

| AT | PKS模块的一部分 A part of the PKS |

由一个或两个独立基因编码的离散型AT A discrete AT encoded by one or two independent genes |

[18] |

| KS | 具有很高的相似性 Have high similarity |

具有底物特异性 Have specificity for their substrates |

[19] |

| KS0 | 罕见 Rare |

常见 common |

[19] |

| β-branch | 罕见 Rare |

常见 common |

[20] |

| ACP | 一个cis-AT只作用于一个ACP A cis-AT acts on one ACP |

一个trans-AT作用于多个ACP A trans-AT acts on multiple ACPs |

[21] |

虽然聚酮类化合物在治疗人类疾病方面有着稳固的作用,但近年来聚酮类药物的发现和开发力度有所减弱[21]。截至目前,对PKS进行工程操作的目的是了解分子结构、产生新的分子化合物、生产已知化合物的类似物及提高产品活性或产率,这种工程操作是制备功能更加优越的聚酮类化合物的一种很有前景的方法[22-23]。

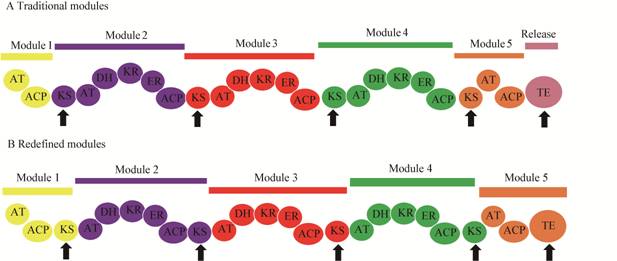

生物合成基因簇的进化可为PKS工程提供参考。多年来,I型PKS模块的概念被广泛使用,其结构为KS+AT (+DH+ER+KR)+ACP(+TE)。通过研究产生氨基多元醇的美迪霉素、新美迪霉素、ECO-02301和新四纤霉素的PKS模块,发现KS域位于每个模块加工酶的下游而不是上游[24]。于是建议重新定义PKS模块为AT+(DH+ER+KR)+ ACP+KS[25](图 2),尽管该模型仍需与PKS演化的其他当前模型相联系,但越来越多的证据表明,修订后的模块有利于工程研究,生物信息学分析也表明该模块同样适用于trans-AT型PKS[26-27]。

|

| 图 2 I型聚酮合成酶模块定义的修正 Figure 2 The revision of type I PKS module definition |

|

|

随着研究者们的深入研究,PKS工程也取得了相应进展,如通过定点突变PikAT5和PikAT6 (皮克罗霉素的AT域)第1次使用2个非天然延长剂单元合成全长聚酮[28];通过交叉互补使用亲合的KirCII (一种trans-AT)将烯丙基和炔丙基官能团引入基罗霉素[29],炔丙基的引入使合成生物学和合成化学相结合,实现天然产物结构的多样化;通过截断PKS模型系统LipPKS1-TE (脂霉素PKS的第1个模块融合来自DEBS的TE)中的还原影响立体化学从反式到合成式的变化[30];用Borrelidin DH2域替换了己二酸PKS组装线中的DH域,实现己二酸的产生,目前该研究正试图通过PKS工程来实现化学品己二酸的体外生产[31]。

PKS工程研究中也有了一些新的发现。例如:(1) trans-AT保留了cis-AT同系物具有的独特的2个亚域α/β水解酶铁氧体蛋白域折叠,并且存在2个酶家族共有的底物特异性的决定因素,所以许多控制cis-AT的分子工具可适用于trans-AT[32-33]。(2) 与cis-AT不同,在trans-AT型PKS系统中,trans-AT作用于多个ACP,如雷纳霉素[34]和艰难梭菌素[21],这表明在整个聚酮化合物内可以使用不同的延长剂单元。因此,通过trans-AT结构域的靶向诱变产生多个变异、非天然的聚酮类化合物具有很大的潜力。(3) β-分支在trans-AT聚酮类化合物中普遍存在,但在cis-AT型聚酮类化合物中较少观察到。最近的一项研究表明,在已知存在β-分支的聚酮类化合物莫匹罗星合成中,ACP中有一个保守序列用于β-分支的形成[35]。因此,为了在聚酮链内的指定位置产生β-分支,可将与β-分支形成相关的ACP重新定位到其起始PKS的替代模块中,或将其他HCS盒(与β-分支形成相关的一组酶的统称)转移到异源系统中。此外,一组独特的结构域KS-B-ACP位于一个合酶模块中,可以催化分支的形成,因此KS-B-ACP在聚酮产品中引入单个β-分支可能比使用HCS盒更具吸引力。

对生物合成途径的研究表明,抗生素是通过cis-AT/trans-AT型PKS和非核糖体肽合成酶(Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase,NRPS)的独特组合合成的[36],从海洋放线菌中可以扩增得到[37-38]。综合相关文献发现,截至目前,通过杂交合成了多种聚酮类化合物,已经观察到结合trans-AT型PKS和NRPS的杂交途径,例如Spliceostatin[39]。此外,还发现了cis-AT/trans-AT型PKS的杂交产物,尽管cis-AT型PKS和trans-AT型PKS的进化起源不同,但它们都采用相同的生物同步原理来组装聚酮产品。因此,在同一个聚酮合酶中cis-AT和trans-AT延伸模块的共存无明显障碍。最近,这种杂交的cis-AT/trans-AT型PKS已经被发现,如Kirromycin[36]和Enacyloxin[40]基因簇也都包含编码cis-AT型和trans-AT型PKS模块的开放阅读框。因此,trans-AT型PKS系统通过基因工程可以将cis-AT型PKS元素结合起来在自然界中共同作用。

3 cis-AT型PKS和trans-AT型PKS的应用cis-AT型PKS装配线目前已经研究得相对透彻,其模块组成类似红霉素的生成模式,而trans-AT型PKS逐渐成为当今的研究热点。此外,杂交的cis-AT/trans-AT型PKS已经被发现,在实际应用中越来越广泛。

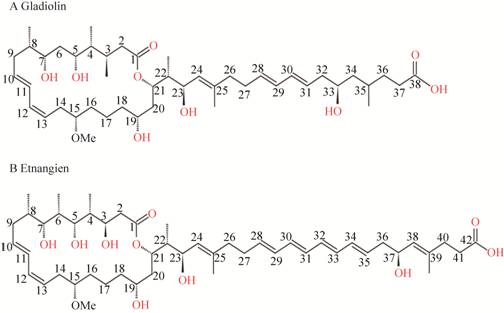

3.1 trans-AT型PKS的应用唐菖蒲苷(Gladiolin)是一种新型大环内酯类抗生素(图 3),可以抑制RNA聚合酶(RNA聚合酶是结核分枝杆菌的有效药物靶点)活性,对结核分枝杆菌H37Rv具有强力的抗菌活性,而且对哺乳动物细胞毒性较低[41]。Etnangien是一种高度不稳定的抗生素,其共轭的无环己烯部分易发生光诱导异构化和快速氧化降解[42],唐菖蒲苷具有较短且更饱和的C-21侧链(含有己烯部分)而优于Etnangien,因此它是一种潜在的候选药物[41]。

|

| 图 3 唐菖蒲苷(A)和Etnangien (B)结构的比较 Figure 3 Comparison of the structure of gladiolin (A) and etnangien (B) |

|

|

唐菖蒲蛋白基因簇包含6个编码trans-AT型PKS的基因,命名为gbn D1−D6,其两侧是编码聚酮加工酶和相关蛋白的多个基因;基因簇中gbnB、gbnN和gbnP编码形成3种trans-AT酶,GbnN和GbnP对丙二酰辅酶A有特异性,但GbnB对唐菖蒲琥珀酰辅酶A具有特异性[41];唐菖蒲苷的生物合成是通过GbnB催化琥珀酰基从琥珀酰辅酶A转移到KS结构域下游的任一ACP结构域,随后将琥珀酰单元反向转移到KS的活性位点Cys上,在琥珀酰起始单元通过与丙二酰扩链剂单元的脱羧基缩合延伸之后,丙二酰扩链剂单元被GbnN加载到KS结构域下游的一个ACP结构域上[43]。此外,由gbnG、gbnF、gbnH和gbnI-J/gbnR-S编码的羟甲基戊二酰辅酶A合成酶被分配到模块1和模块6中形成β-甲基分支[35]。唐菖蒲苷生物合成途径具有20个KS结构域,但是从琥珀酰辅酶A起始单元和16个丙二酰辅酶A延伸单元组装聚酮链只需要17个链延伸反应[41]。因此,其中3个KS结构域必须充当AT的功能,将聚酮链从一个ACP转移到另一个ACP。在其他trans-AT型PKS途径中,这种转酰基反应通常由KS0结构域催化,KS0结构域缺少HGTGT基序的组氨酸残基,而HGTGT基序是催化链延伸所必需的[44]。

3.2 杂合cis-AT/trans-AT PKS的应用依那昔洛辛(Enacyloxin)是一种独特的多羟基多烯类黄色抗生素,最初从C-变形杆菌Frateuria sp. W-315中分离得到[45],其通过抑制核糖体释放EF-Tu-GDP来抑制肽的生物合成,从而对G+和G–细菌具有较强抑菌活性,同时对真菌也有较弱活性,但对酵母无显著影响[46]。

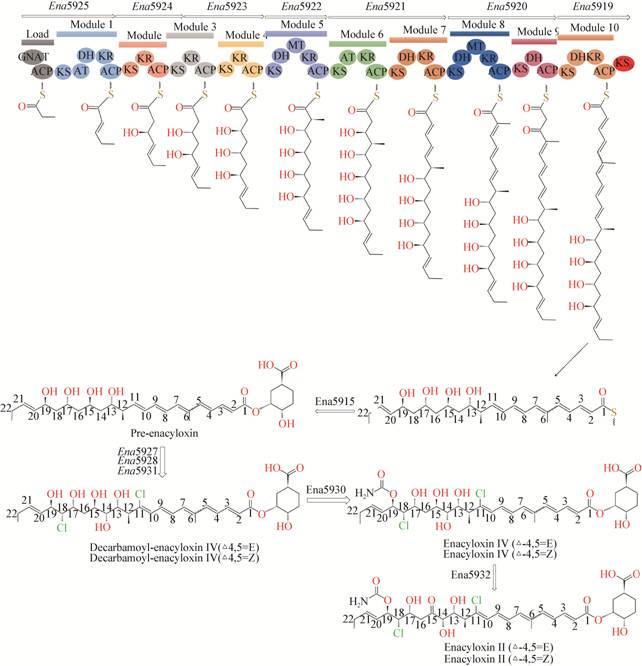

Enacyloxin基因簇编码一个cis-AT/trans-AT型PKS,包含21个基因[47],其中基因ena5920–ena5925负责模块化PKS,包括1个加载模块和9个链延伸模块(图 4)。在Enacyloxin Ⅱ生物合成途径中,加载模块中的类N-乙酰基转移酶结构域(GNAT)催化甲基丙二酰辅酶A脱羧,在GNAT相邻的ACP结构域上生成起始单元丙酰辅酶A;链延伸模块中的AT域仅存在于模块1和6中,而在模块2−5和7−10中缺失,同时其他基因簇内也不编码AT[47]。因此,在模块1和6的AT域可能负责将丙二酰辅酶A延长剂单元转移到ACP结构域上。

|

| 图 4 依那昔洛辛Ⅱ生物合成途径 Figure 4 Biosynthesis pathway of enacyloxinⅡ |

|

|

bamb_6476和bamb_0998位于Enacyloxin基因簇之外,是编码可能有助于Enacyloxin合成的结构域的候选基因,二者在Enacyloxin诱导条件下表达[48],因此,Enacyloxin的生物合成可能以复杂的方式涉及各种反式AT酶。Enacyloxin II具有异构体,通过PKS模块10内酮基的还原和水的消除,产生了具有△4, 5几何构型的Enacyloxin IIa异构体的混合物;模块10内还有一个KS0域,该域催化聚酮链从模块10转移到由ena5917编码的另一个ACP域,之后,共线聚酮与(1S, 3R, 4S)-3, 4-二羟环己烷羧酸(简称DHCCA)的C-3羟基缩合,通过聚酮链释放的不寻常机制形成前依那昔洛辛[49]。DHCCA由莽草酸合成,莽草酸是芳香族氨基酸生物合成的中间产物,通过ena5916、ena5914、ena5912和ena5918编码的酶合成[47]。前依那昔洛辛通过卤代酶的严格反应转化为去甲酰氧基Enacyloxin IVa和异癸甲酰烯丙氧基Enacyloxin IVa;然后,去甲酰氧基Enacyloxin IVa经ena5930编码的氨甲酰转移酶催化生成Enacyloxin IVa;Enacyloxin IVa通过氧合酶的催化转化为Enacyloxin IIa[50]。

4 目前存在的问题与展望虽然目前I型PKS已应用于生物燃料和工业化学品等方面,但依旧存在一些难以解决的问题:(1) 许多KS域具有严格的底物特异性,转化后异源模块杂交PKS的上游模块的ACP与其非同源性的KS结构域之间新生酰基链的转移效率发生改变,导致聚酮化合物合成的失败或效率降低[24, 51-52];(2) KR结构域被描述为PKS装配线的“立体化学主力”。然而,截至目前仅在截断模型系统中证明了实现立体化学变化的KR结构域交换,即:要获得有效的酮还原和甲基立体化学的改变,需要在PKS系统之间交换完整的模块,而不仅仅是负责的KR结构域[53];(3) 对PKS中模块化边界和各种蛋白质-蛋白质相互作用的理解还不够深入,导致I型PKS模块替换可能会显著改变整个催化结构域或造成模块结构的稳定性被破坏,从而损害PKS的所有催化功能[10, 54]。

展望未来,新的高通量合成大DNA片段以编辑微生物基因组的方法,以及自动筛选大量表达菌株将加快杂合NRPS-PKS重组的速度[55]。另外,使用新颖的方法,如合成亮氨酸拉链来取代天然PKS中的连接域将促进聚酮合酶的重新设计[56];基于无细胞生物合成的策略扩大了合理设计新PKS的范围[57];最近开发的计算工具ClusterCAD也可用于PKS和模块从头生成感兴趣的化合物[58],这些新颖的方法和技术都表明cis-AT型PKS和trans-AT型PKS工程的前景仍十分光明。

| [1] |

Fan RL, Chen K, Zhu JW, Yu LJ. Preparation of rifamycin S by oxidation of rifamycin SV[J]. Chemical Engineering (China), 2018, 46(10): 51-55. (in Chinese) 范若兰, 陈葵, 朱家文, 于丽君. 利福霉素SV氧化制备利福霉素S工艺研究[J]. 化学工程, 2018, 46(10): 51-55. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-9954.2018.10.011 |

| [2] |

Liu J, Zhao ZH, Qiu NS, Zhou Q, Wang GW, Jiang HP, Piao Y, Zhou ZX, Tang JB, Shen YQ. Co-delivery of IOX1 and doxorubicin for antibody-independent cancer chemo-immunotherapy[J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12: 2425. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-22407-6 |

| [3] |

Wang L, Yuan MJ, Zheng JT. Crystal structure of the condensation domain from lovastatin polyketide synthase[J]. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology, 2019, 4(1): 10-15. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2018.11.003 |

| [4] |

Li ZY, Su LJ, Wang HZ, An SH, Yin XM. Physicochemical and biological properties of nanochitin — abamectin conjugate for Noctuidae insect pest control[J]. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 2020.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-020-05015-1

|

| [5] |

Hu MJ, Xia HY, Qin CJ. Effects on productivity of avermectin by knockout of 10 polyketide biosynthetic gene clusters in Streptomyces avermitilis genome[J]. Microbiology China, 2014, 41(7): 1471-1476. (in Chinese) 胡敏杰, 夏海洋, 覃重军. 除虫链霉菌10个聚酮类抗生素生物合成基因簇的敲除对阿维菌素产量的影响[J]. 微生物学通报, 2014, 41(7): 1471-1476. |

| [6] |

Weissman KJ. Genetic engineering of modular PKSs: from combinatorial biosynthesis to synthetic biology[J]. Natural Product Reports, 2016, 33(2): 203-230. DOI:10.1039/C5NP00109A |

| [7] |

Zhang B, Zhou YT, Huang K, Fan LG, Liu ZQ. Research progress of regulators in polyene macrolide antibiotic biosynthetic gene clusters[J]. Microbiology China, 2019, 46(1): 172-183. (in Chinese) 张博, 周奕腾, 黄恺, 樊林鸽, 柳志强. 多烯大环内酯类抗生素生物合成基因簇中调控因子的研究进展[J]. 微生物学通报, 2019, 46(1): 172-183. |

| [8] |

Zhang B, Xiang WS. Advances in cis-AT and trans-AT polyketide synthases and their special domains[J]. Journal of Northeast Agricultural University, 2016, 47(1): 87-92. (in Chinese) 张博, 向文胜. Cis-AT和Trans-AT聚酮合酶及其特殊功能域研究进展[J]. 东北农业大学学报, 2016, 47(1): 87-92. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-9369.2016.01.013 |

| [9] |

Feng JF, Zhou RC, Guo XT, Zhang Y. Polyketide and its application[J]. Modern Agricultural Sciences and Technology, 2011(3): 24-26. (in Chinese) 冯健飞, 周日成, 郭兴庭, 张扬. 聚酮类化合物及其应用[J]. 现代农业科技, 2011(3): 24-26. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-5739.2011.03.005 |

| [10] |

Drufva EE, Hix EG, Bailey CB. Site directed mutagenesis as a precision tool to enable synthetic biology with engineered modular polyketide synthases[J]. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology, 2020, 5(2): 62-80. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2020.04.001 |

| [11] |

Kapur S, Lowry B, Yuzawa S, Kenthirapalan S, Chen AY, Cane DE, Khosla C. Reprogramming a module of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase for iterative chain elongation[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(11): 4110-4115. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1118734109 |

| [12] |

Koryakina I, Kasey C, McArthur JB, Lowell AN, Chemler JA, Li SS, Hansen DA, Sherman DH, Williams GJ. Inversion of extender unit selectivity in the erythromycin polyketide synthase by acyltransferase domain engineering[J]. ACS Chemical Biology, 2017, 12(1): 114-123. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.6b00732 |

| [13] |

Piel J. Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases[J]. Natural Product Reports, 2010, 27(7): 996-1047. DOI:10.1039/b816430b |

| [14] |

Cheng YQ, Tang GL, Shen B. Type I polyketide synthase requiring a discrete acyltransferase for polyketide biosynthesis[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2003, 100(6): 3149-3154. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0537286100 |

| [15] |

Jenner M, Afonso JP, Bailey HR, Frank S, Kampa A, Piel J, Oldham NJ. Acyl-chain elongation drives ketosynthase substrate selectivity in trans-acyltransferase polyketide synthases[J]. Angewandte Chemie: International Ed in English, 2015, 54(6): 1817-1821. DOI:10.1002/anie.201410219 |

| [16] |

Wright GD. Christopher Walsh: Pioneer and innovator in antibiotic and natural product chemical biology[J]. The Journal of Antibiotics, 2014, 67(1): 5-6. DOI:10.1038/ja.2013.118 |

| [17] |

Wagner DT, Zhang ZC, Meoded RA, Cepeda AJ, Piel J, Keatinge-Clay AT. Structural and functional studies of a pyran synthase domain from a trans-acyltransferase assembly line[J]. ACS Chemical Biology, 2018, 13(4): 975-983. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.8b00049 |

| [18] |

Jenner M, Frank S, Kampa A, Kohlhaas C, Pöplau P, Briggs GS, Piel J, Oldham NJ. Substrate specificity in ketosynthase domains from trans-AT polyketide synthases[J]. Angewandte Chemie: International Ed in English, 2013, 52(4): 1143-1147. DOI:10.1002/anie.201207690 |

| [19] |

Kohlhaas C, Jenner M, Kampa A, Briggs GS, Afonso JP, Piel J, Oldham NJ. Amino acid-accepting ketosynthase domain from a trans-AT polyketide synthase exhibits high selectivity for predicted intermediate[J]. Chemical Science, 2013, 4(8): 3212-3217. DOI:10.1039/c3sc50540e |

| [20] |

Helfrich EJN, Piel J. Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases[J]. Natural Product Reports, 2016, 33(2): 231-316. DOI:10.1039/C5NP00125K |

| [21] |

Al-Dhelaan R, Russo PS, Padden SE, Amaya A, Dong DW, You YO. Condensation-incompetent ketosynthase inhibits trans-acyltransferase activity[J]. ACS Chemical Biology, 2019, 14(2): 304-312. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.8b01043 |

| [22] |

Porterfield WB, Poenateetai N, Zhang WJ. Engineered biosynthesis of alkyne-tagged polyketides by type I PKSs[J]. iScience, 2020, 23(3): 100938. DOI:10.1016/j.isci.2020.100938 |

| [23] |

Miyazawa T, Hirsch M, Zhang ZC, Keatinge-Clay AT. An in vitro platform for engineering and harnessing modular polyketide synthases[J]. Nature Communications, 2020, 11: 80. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-13811-0 |

| [24] |

Zhang LH, Hashimoto T, Qin B, Hashimoto J, Kozone I, Kawahara T, Okada M, Awakawa T, Ito T, Asakawa Y, et al. Characterization of giant modular PKSs provides insight into genetic mechanism for structural diversification of aminopolyol polyketides[J]. Angewandte Chemie: International Ed in English, 2017, 56(7): 1740-1745. DOI:10.1002/anie.201611371 |

| [25] |

Keatinge-Clay AT. Polyketide synthase modules redefined[J]. Angewandte Chemie: International Ed in English, 2017, 56(17): 4658-4660. DOI:10.1002/anie.201701281 |

| [26] |

Nivina A, Yuet KP, Hsu J, Khosla C. Evolution and diversity of assembly-line polyketide synthases[J]. Chemical Reviews, 2019, 119(24): 12524-12547. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00525 |

| [27] |

Vander Wood DA, Keatinge-Clay AT. The modules of trans-acyltransferase assembly lines redefined with a central acyl carrier protein[J]. Proteins, 2018, 86(6): 664-675. DOI:10.1002/prot.25493 |

| [28] |

Kalkreuter E, CroweTipton JM, Lowell AN, Sherman DH, Williams GJ. Engineering the substrate specificity of a modular polyketide synthase for installation of consecutive non-natural extender units[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019, 141(5): 1961-1969. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b10521 |

| [29] |

Musiol-Kroll EM, Zubeil F, Schafhauser T, Härtner T, Kulik A, McArthur J, Koryakina I, Wohlleben W, Grond S, Williams GJ, et al. Polyketide bioderivatization using the promiscuous acyltransferase KirCII[J]. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2017, 6(3): 421-427. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.6b00341 |

| [30] |

Eng CH, Yuzawa S, Wang G, Baidoo EEK, Katz L, Keasling JD. Alteration of polyketide stereochemistry from anti to syn by a ketoreductase domain exchange in a type I modular polyketide synthase subunit[J]. Biochemistry, 2016, 55(12): 1677-1680. DOI:10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00129 |

| [31] |

Hagen A, Poust S, Rond TD, Fortman JL, Katz L, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD. Engineering a polyketide synthase for in vitro production of adipic acid[J]. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2016, 5(1): 21-27. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.5b00153 |

| [32] |

Yuzawa S, Keasling JD, Katz L. Bio-based production of fuels and industrial chemicals by repurposing antibiotic-producing type I modular polyketide synthases: opportunities and challenges[J]. The Journal of Antibiotics, 2017, 70(4): 378-385. DOI:10.1038/ja.2016.136 |

| [33] |

Till M, Race PR. Progress challenges and opportunities for the re-engineering of trans-AT polyketide synthases[J]. Biotechnology Letters, 2014, 36(5): 877-888. DOI:10.1007/s10529-013-1449-2 |

| [34] |

Pan GH, Xu ZR, Guo ZK, Hindra, Ma M, Yang D, Zhou H, Gansemans Y, Zhu XC, Huang Y, et al. Discovery of the leinamycin family of natural products by mining actinobacterial genomes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2017, 114(52): E11131-E11140. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1716245115 |

| [35] |

Haines AS, Dong X, Song ZS, Farmer R, Williams C, Hothersall J, Płoskoń E, Wattana-Amorn P, Stephens ER, Yamada E, et al. A conserved motif flags acyl carrier proteins for β-branching in polyketide synthesis[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2013, 9(11): 685-692. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.1342 |

| [36] |

Robertsen HL, Musiol-Kroll EM, Ding L, Laiple KJ, Hofeditz T, Wohlleben W, Lee SY, Grond S, Weber T. Filling the gaps in the kirromycin biosynthesis: Deciphering the role of genes involved in ethylmalonyl-CoA supply and tailoring reactions[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8(1): 3230. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-21507-6 |

| [37] |

Xue YC, Zhang CS, Li G. Cloning and analysis of the adenylation domain of nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2019, 39(1): 20-25. (in Chinese) 薛永常, 张成锁, 李根. 非核糖体肽合成酶基因腺苷酰化结构域序列克隆及分析[J]. 微生物学杂志, 2019, 39(1): 20-25. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-7021.2019.01.003 |

| [38] |

Li G, Xue YC. Cloning of nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene condensation domain fragment[J]. Industrial Microbiology, 2017, 47(2): 37-42. (in Chinese) 李根, 薛永常. 非核糖体肽合成酶缩合结构域基因片段克隆[J]. 工业微生物, 2017, 47(2): 37-42. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-6678.2017.02.007 |

| [39] |

Eustáquio AS, Janso JE, Ratnayake AS, ODonnell CJ, Koehn FE. Spliceostatin hemiketal biosynthesis in Burkholderia spp. is catalyzed by an iron/α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(33): E3376-E3385. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1408300111 |

| [40] |

Risser F, Collin S, Dos Santos-Morais R, Gruez A, Chagot B, Weissman KJ. Towards improved understanding of intersubunit interactions in modular polyketide biosynthesis: Docking in the enacyloxin IIa polyketide synthase[J]. Journal of Structural Biology, 2020, 212(1): 107581. DOI:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107581 |

| [41] |

Song LJ, Jenner M, Masschelein J, Jones C, Bull MJ, Harris SR, Hartkoorn RC, Vocat A, Romero-Canelon I, Coupland P, et al. Discovery and biosynthesis of gladiolin: A Burkholderia gladioli antibiotic with promising activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2017, 139(23): 7974-7981. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b03382 |

| [42] |

Altendorfer M, Raja A, Sasse F, Irschik H, Menche D. Modular synthesis of polyene side chain analogues of the potent macrolide antibiotic etnangien by a flexible coupling strategy based on hetero-bis-metallated alkenes[J]. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2013, 11(13): 2116-2139. |

| [43] |

Nguyen T, Ishida K, Jenke-Kodama H, Dittmann E, Gurgui C, Hochmuth T, Taudien S, Platzer M, Hertweck C, Piel J. Exploiting the mosaic structure of trans-acyltransferase polyketide synthases for natural product discovery and pathway dissection[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2008, 26(2): 225-233. DOI:10.1038/nbt1379 |

| [44] |

Huang Y, Tang GL, Pan GH, Chang CY, Shen B. Characterization of the ketosynthase and acyl carrier protein domains at the LnmI nonribosomal peptide synthetase-polyketide synthase interface for leinamycin biosynthesis[J]. Organic Letters, 2016, 18(17): 4288-4291. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02033 |

| [45] |

Watanabe T, Sugiyama T, Takahashi M, Jun SM, Yamashita K, Izaki K, Furihata K, Seto H. New polyenic antibiotics active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. IV. Structural elucidation of enacyloxin IIa[J]. The Journal of Antibiotics, 1992, 45(4): 470-475. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.45.470 |

| [46] |

Cetin R, Krab IM, Anborgh PH, Cool RH, Watanabe T, Sugiyama T, Izaki K, Parmeggiani A. Enacyloxin IIa, an inhibitor of protein biosynthesis that acts on elongation factor Tu and the ribosome[J]. The EMBO Journal, 1996, 15(10): 2604-2611. DOI:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00618.x |

| [47] |

Mahenthiralingam E, Song LJ, Sass A, White J, Wilmot C, Marchbank A, Boaisha O, Paine J, Knight D, Challis GL. Enacyloxins are products of an unusual hybrid modular polyketide synthase encoded by a cryptic Burkholderia ambifaria genomic island[J]. Chemistry & Biology, 2011, 18(5): 665-677. |

| [48] |

Kosol S, Gallo A, Griffiths D, Valentic TR, Masschelein J, Jenner M, De Los Santos ELC, Manzi L, Sydor PK, Rea D, et al. Structural basis for chain release from the enacyloxin polyketide synthase[J]. Nature Chemistry, 2019, 11(10): 913-923. DOI:10.1038/s41557-019-0335-5 |

| [49] |

Masschelein J, Sydor PK, Hobson C, Howe R, Jones C, Roberts DM, Yap ZL, Parkhill J, Mahenthiralingam E, Challis GL. A dual transacylation mechanism for polyketide synthase chain release in enacyloxin antibiotic biosynthesis[J]. Nature Chemistry, 2019, 11(10): 906-912. DOI:10.1038/s41557-019-0309-7 |

| [50] |

Chen HN, Bian ZL, Ravichandran V, Li RJ, Sun Y, Huo LJ, Fu J, Bian XY, Xia LQ, Tu Q, et al. Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases in Burkholderiales[J]. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 2019, 45(2): 162-181. DOI:10.1080/1040841X.2018.1514365 |

| [51] |

Keatinge-Clay AT. Stereocontrol within polyketide assembly lines[J]. Natural Product Reports, 2016, 33(2): 141-149. DOI:10.1039/C5NP00092K |

| [52] |

Murphy AC, Hong H, Vance S, Broadhurst RW, Leadlay PF. Broadening substrate specificity of a chain-extending ketosynthase through a single active-site mutation[J]. Chemical Communications, 2016, 52(54): 8373-8376. DOI:10.1039/C6CC03501A |

| [53] |

Annaval T, Paris C, Leadlay PF, Jacob C, Weissman KJ. Evaluating ketoreductase exchanges as a means of rationally altering polyketide stereochemistry[J]. ChemBioChem, 2015, 16(9): 1357-1364. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201500113 |

| [54] |

Yuzawa S, Deng K, Wang G, Baidoo EEK, Northen TR, Adams PD, Katz L, Keasling JD. Comprehensive in vitro analysis of acyltransferase domain exchanges in modular polyketide synthases and its application for short-chain ketone production[J]. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2017, 6(1): 139-147. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.6b00176 |

| [55] |

Tong YJ, Weber T, Lee SY. CRISPR/Cas-based genome engineering in natural product discovery[J]. Natural Product Reports, 2019, 36(9): 1262-1280. DOI:10.1039/C8NP00089A |

| [56] |

Klaus M, D'Souza AD, Nivina A, Khosla C, Grininger M. Engineering of chimeric polyketide synthases using SYNZIP docking domains[J]. ACS Chemical Biology, 2019, 14(3): 426-433. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.8b01060 |

| [57] |

Huang HM, Stephan P, Kries H. Engineering DNA-templated nonribosomal peptide synthesis[J]. Cell Chemical Biology, 2021, 28(2): 221-227.e7. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.11.004 |

| [58] |

Eng CH, Backman TWH, Bailey CB, Magnan C, García Martín H, Katz L, Baldi P, Keasling JD. ClusterCAD: a computational platform for type I modular polyketide synthase design[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2018, 46(D1): D509-D515. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkx893 |

2021, Vol. 48

2021, Vol. 48